Archetypal "unity is a circle flattened ellipse" picture from Unsplash

Before I get into the post, I think it would be useful to explain where exactly my viewpoint is coming from, because there is an insidious tendency I've noticed when it comes to subjective accounts, in which people extrapolate the account/attach extra reliability just because it's different from their own experience. After all, I am but one person, and my experiences aren't always representative of everyone's...

So let me begin. Although I was born and raised in the U.S., my parents are both immigrants from a country dominated by (mostly though not exclusively) British colonialism for over a century. We still visit relatively often—usually around once a year—and I'm relatively well-connected with the culture of the region of the country my parents were born and raised in. This connection takes the typical forms of food, language, religious values and observances, etc., but some of the socio-cultural values have also drifted over. To some extent, these values have simply been transplanted and allowed to compete against the values of the part of the U.S. where I live, but the more interesting case is of those values that I don't necessarily share but am keenly aware of.

Behavior around anything remotely academic is one example, and a case that forms the basis of my views on a pan-human language. I'm well-oriented with code-switching, even if I didn't know it by that term until relatively recently. (For the unacquainted, code-switching is a multilingual phenomenon involving switching from one language to another during a conversation, depending on the context.) Typically, we—and other people from the same country—switch to English when discussing more intellectual subjects.

This isn't at all surprising, but it's still problematic. I say it's expected because the discovery of ideas and knowledge is closely tied to history. It's reasonable that Western European languages would have more knowledge and nomenclature built into them because Western Europe (and certain offshoots, e.g. the U.S.) has been behind much of academic discovery in the past few centuries. Therefore, those languages tend to be better at expressing those academic ideas, and naturally code-switching results.

This, unfortunately, comes with negative consequences for other languages, as well as arguably an unintentional promotion of the colonial state of affairs: under colonialism, intellectuals used the language(s) of the ruling colonizer class, so can we really claim practical progress if the goal in education is still to learn the former colonial language(s) to obtain a job/study at higher levels/contribute in a knowledge-based occupation? It's also damaging to national psyche to place so much importance on a language from a distant country. (Again, this is admittedly speculative and based on my own experience and perception of people I've interacted with, and absolute arguments generally fail anyway, although I still think this is a reasonable statement to make.)

But there's another reason for a pan-human language that I think is even more compelling.

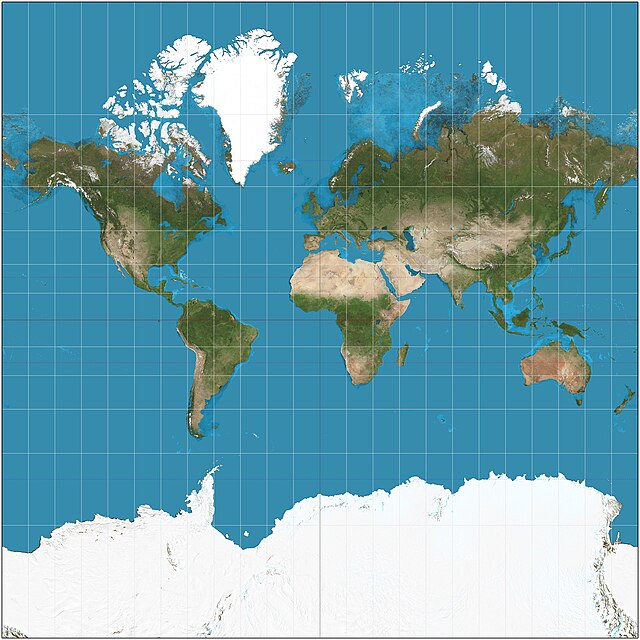

Wikimedia Commons picture of a Mercator map , a.k.a. the Comic Sans of cartography

The New Paradigm

Humans have, for the most part, prioritized increasing global cooperation in the past few years. Despite what tech startup CEOs would like us to think, true "revolutionary" and "disruptive" "paradigm shifts" are not so common, because it takes a lot to change the consensus philosophy. But I would argue that a true paradigm shift has taken place with how we view other countries, at least politically. No longer can countries get away with conquest without risking international consequences. As an example: if for whatever reason Brazil (population over 215 million, army with 235,000 active) decided to absorb Suriname (population about 600,000, army with 2,000 active), it probably could. But it wouldn't, because that would draw international condemnation. For that matter, the U.S. could probably conquer any Caribbean country if it really wanted to (I mean, the U.S. does have nuclear weapons), except it wouldn't, because that would run astray of the will of the combined international powers that is the U.N.

Whether it's because it's more beneficial to cooperate or whether zero-sum expansion is just not worth being alienated by the rest of the world (or even because countries care more about people's rights, although I remain skeptical), there is largely a sense, at least in the West, that international cooperation = good.

And common sense would agree! It's like the old saying goes: 8 billion heads are better than however many your country has.

So then, the potential benefits of a pan-human language should be clear: if you eliminate language barriers, then suddenly it becomes a lot easier for researchers to communicate with each other and build on others' research. Or, for that matter, for political leaders! Or for businesspeople! Or really any institutional profession that involves talking to people who may not speak the same language. There's a lot of different ways a pan-human language would benefit us.

Picture of "caveat" as according to Wikimedia Commons

Caveat Lector

I feel pretty strongly that any potential lingua franca should be completely new and not a language that is currently spoken, for a few particular reasons. First of all, there is incredible variety from one language to the other, and I think we'd lose a lot of culture, poetry, and expression if we supplanted them all with one pre-existing language... not to mention that invasively imposing a worldwide standard is EXTREMELY immoral and impractical. On a similar note, every language has flaws or areas that are illogical/more complicated than they need to be, so if you're going to go through the effort of implementing a pan-human language, why settle for less than optimal?

If we do employ a common language, as I think we should, the least destructive option (in that it maintains the same benefits but doesn't have all of the drawbacks) is an informationally efficient common language. Ideally, this language would be strongly centralized as well, so that local dialects don't nullify the point of having a shared language. The overall benefits obviously include better communication and efficiency, but truly pushing past colonial languages would be an added incentive. I also think it'd be a natural development of interconnectedness and information, which appears to be a (if not THE) motif of our current historical era, which is beautiful in its own way. I think. I'm a history nerd, so my view is a little biased here.

But, of course, there are substantial downsides, the biggest being practicality. Unfortunately, we as humans have a spectacularly terrible tendency of accepting the adequate because it'd take effort to create something better, like some kind of reverse

sunk cost fallacy. And, of course, it's not like the current system is completely and utterly terrible—there's plenty of room for improvement, but clearly it's working, even if it's not perfect. And admittedly, we'd need a massive effort to put a new language in curriculums (curriculae?) all around the world, as well as in areas with fewer or no education centers.

There's also a valid concern that it wouldn't immediately reduce the reliance on (emphasis on vestigial and replaceable, which excludes deeply culturally ingrained languages like Spanish in South America) colonial languages in previously colonized areas, partly because of the time it would take to restructure society, and partly because incremental changes tend to be more successful than radical all-at-once changes at a larger scale.

The other concern I have is that code-switching is, in some ways, even more incentivized when there's a pan-human language. From the perspective of an individual, the situation isn't that much different from before, except with remnant colonial languages in formerly colonized countries replaced by the new language, so it's possible code-switching could still happen in the same way, just with one language swapped out for another. I do think code-switching is only a problem because it aids colonial ideas to continue, and not because it's inherently bad, but there's also a real danger that it becomes less worthwhile to use preexisting languages. Although my lens could be very off here! It's very hard to predict human attitudes, especially at a cultural or societal level. So my hope is that I'm wrong about these concerns, and preexisting languages will do just fine, with the new unified language serving more as a supplement.

With all of that said, I stand by my view that a pan-human language would not just have more pros than cons, but would be an active improvement to the world. It would take a huge effort, and the potential benefits are very much tied to the current global situation, so I have doubts whether it can/will actually be put into action. But then again, the eradication of smallpox also seemed like an impossible effort, and that goal ended up being achieved! I will continue to hold hope, no matter how small the chance.

Thanks for reading, and I'm really interested to know what your thoughts are!

~Coruscant

Interesting.

ReplyDeleteThe points make sense and the article is well written. Although the language was a bit too complicated for me to understand. Probably just a me problem though.

Delete